In our own right, we are leading change

Written by Kirra, Y-Change Lived Experience Consultant and Youth Focused Peer Support Worker at Take Two’s Northern Healing and Recovery Program (NHARP).

This article is a reflection on the process of bringing the voices of children and young people being supported by NHARP to Family Safety Victoria’s Inaugural Lived Experience Forum.

All the young people who participated in this project have consented to their reflections being shared with the hope for change.

There are so many things that an adult victim survivor may not see or even realise that abuse is happening to children and young people. So, when you block us out and don’t speak to us, you’re not hearing the whole story of abuse. Often children and young people will try and shelter or protect the adult victim survivor from more pain and harm by not telling them about other stuff that has happened.

Children and young people are rarely part of conversations about their experiences of family violence and hard times. We have important stories to share and by not hearing them, people are missing a massive part of the family violence narrative.

Children and young people with a lived experience of disadvantage are activists, advocates, knowledge holders and in our own right, leading change.

The process journey from beginning to end

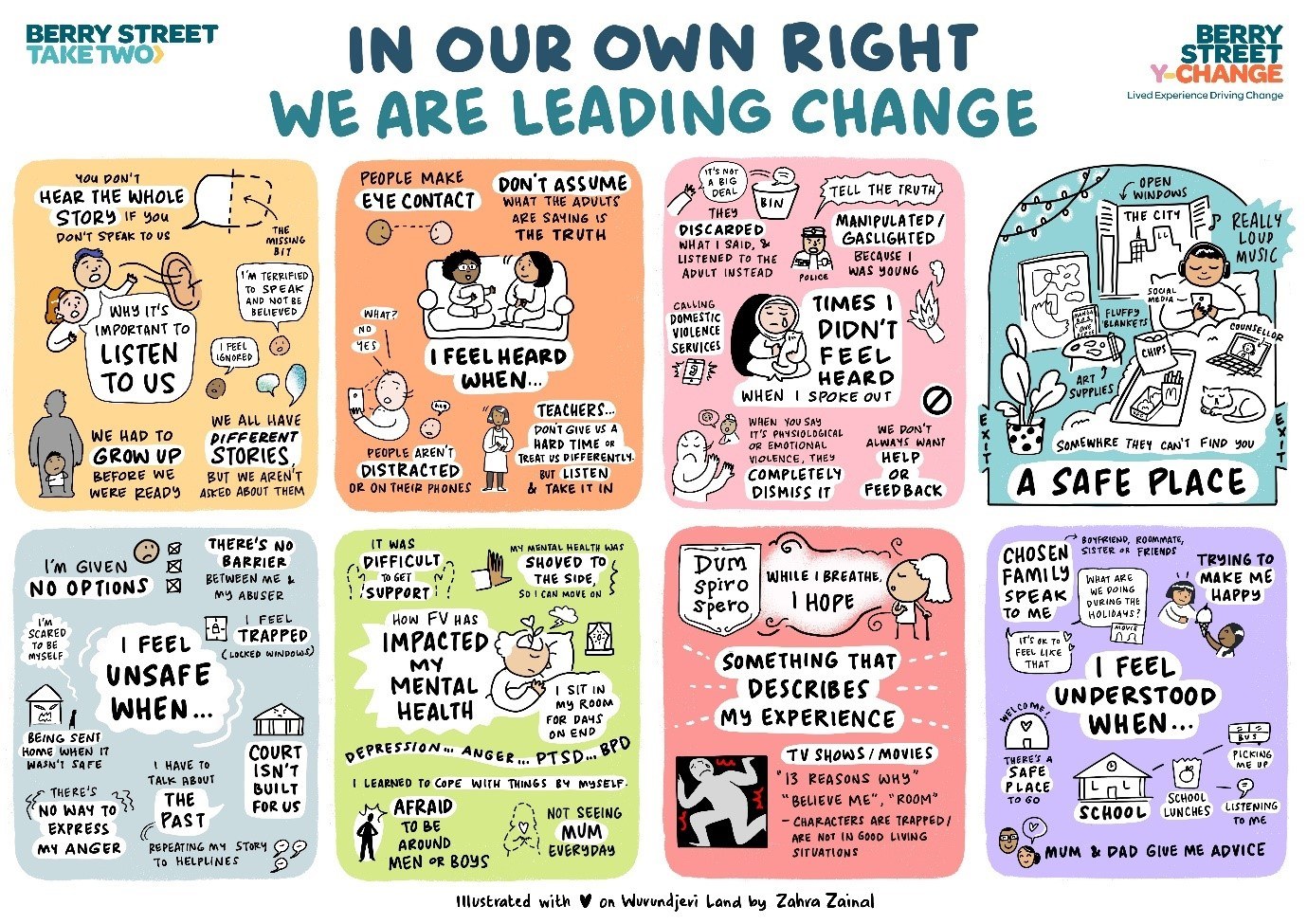

In February 2022, Take Two’s Northern Healing and Recovery Program (NHARP) and Y-Change received funding from Family Safety Victoria to host a series of listening sessions to capture what is important to children and young people when experiencing family violence, and create an illustrated resource from what we heard. Monique Balfour, Take Two Clinician, supported this work, and we combined our professional knowledge and lived experience.

In April 2022, I presented the insights from young victim survivors, as well as my own lived experience, at Family Safety Victoria’s Lived Experience Forum, ‘More than our story: action, wisdom and change’.

COVID-19 causes disruptions to the in-person workshop approach

Our initial idea for the ‘listening sessions’ was to host an in-person workshop for young people aged 10 to 18 with living experiences of family violence within NHARP. We really wanted to hear from children and young people currently accessing NHARP to capture feedback on what’s working and what can be done better.

We also wanted to create a space where young people who are isolated could connect with others who have been through similar experiences. We committed to paying the young people from the beginning, as it’s important to recognise their expertise and time.

We had to pivot when clinicians and young people who were planning to be at the workshop came down sick with COVID. At the same time, many of the young people being supported by NHARP shared that they didn’t feel like it was the right time to be involved in the workshop and that it didn’t feel safe to be part of these conversations.

As our main priority is respecting their right to agency and in making their own decisions, we decided to rethink our initial idea of the in-person workshop.

Listening and responding to young people with lived experience

The nature of family violence takes so much physical and psychological safety away from young people. The harsh reality is that a lot of children and young people are still forced by the courts and the adults in their lives to see people who use violence, even if they don’t want to. Often these decisions are being made about young people in courts without knowing what their experiences of family violence are. Not being included in decisions about their lives can leave young people feeling powerless, often paralleling the experiences of family violence. For some children and young people, there is also ongoing family violence risk and coercive control, even after parents have separated – violence doesn’t always end once a relationship does.

After listening to the young people’s feedback about the in-person workshop, we shifted our approach by offering:

- both in-person and online options

- options of meeting in a group or individually

- to meet with a peer support worker (me) present or just with their clinician; and

- more creative options for answering the questions – through writing and drawing and then sending through to us.

In offering different ways of being part of the project, young people could choose how to be best involved in creating change.

We ran one group session that ended up being for young people aged 10 to 12 and a few individual sessions for young people aged 18 to 22. We had conversations about the importance of listening to children and young people, changes they wanted to see in the broader system, the impact family violence has on their mental health, and what makes them feel both safe and unsafe. We wanted to make the process as accessible as possible and we knew for every young person would look different.

Graphic recorder captures meaningful contributions in real-time

We had a graphic recorder (or live scribe), Zahra Zainal, attend one of the workshops. A graphic recorder’s role is to capture key themes from our discussion and then combine and document them meaningfully in a visual form.

Through working with a graphic recorder, the young people could see what they contributed being illustrated in real-time. This helped foster a feeling of purpose and validation, knowing that what was being captured would be shared at Family Safety Victoria’s Lived Experience Forum.

This process was led by me, a Peer Worker, and I really focused on building reciprocal relationships with the young people. Peer work is not just about the lived experience that I bring but also about what I learn from others and what we can create together. This process created safety and meant young people didn’t have to go into the detail of their experiences but also allowed them the space to share their wisdom and insights.

Engaging a graphic recorder is just one example of how to meaningfully engage with children and young people who are currently accessing services. There are many ways that children and young people can be heard now, instead of waiting until they aren’t in services anymore.

Reflecting on the challenges, surprises and key learnings

It was really challenging hearing how many times the service system has further harmed children and young people with living experiences of family violence, as well as how what’s being done isn’t enough.

Change is needed and it is needed now. Children and young people need to be partnered with to create the change we want to see in the world. We are not alone in our feelings of frustration with the system and our experiences.

Some parents say this generation is stuffed up. Some parents say, ‘I got smacked when I was a child and I turned out okay’. Just because you were hit when you were younger does not mean you can smack us.

This really hit home, reflecting on the ongoing cycle of violence and intergenerational trauma. Other ways of using discipline do not involve violence, like talking directly with children and young people. The young people we spoke with also suggested getting smacked less and not on the face, as some sort of improvement to the violence they are currently experiencing. Family violence can become normalised for young victim survivors, contributing to intergenerational violence.

I wish parents would listen to other people’s emotions. [Other family members] have feelings too, some parents are self-centred and care only about themselves. The world doesn’t revolve around you.

Young people, especially those under the age of 18, are often not involved or spoken to at all because of perceived risk. By not including and speaking to children and young people, it is more of a risk to our safety as workers, organisations and systems, as we are missing such a big part of the story.

It’s true that there are often barriers, but as we’ve shown through facilitating this process, speaking with children and young people with a lived experience can be done safely and in an accessible and organic way. Children and young people can be straight to the point, there’s no messing around – often it is adults’ anxiety and not doing the internal work required that is the barrier to truly listening to and supporting us.

I was at the police station in 2020. I went there because my dad was being really abusive. So, I ran off. When I got there, they said, ’Do you want to tell me the truth of what’s really going on?’ I burst into tears because I wouldn’t be there if I felt like I was safe, and they discarded what I said and listened to the adults instead of me. At the time I was around 16. I didn’t feel listened to.

The young people we connected with talked a lot about not being believed, about workers and the police prioritising and trusting adults’ voices over theirs. Often the person using violence was believed over the young person, as they would manipulate the situation and blame the young person for reacting to the violence.

Violence is not the answer to anything, violence sucks. It does nothing but make the situation worse.

By listening to what children and young people have shared with us, we will continue to provide this opportunity to speak with a Peer Worker about their lived experience. We are also writing to Family Safety Victoria to ask for more funding to do another live illustration and hear from more children and young people with lived expertise. It’s essential to listen to young victim survivors in the system and connect with them when they are ready. We are doing this to keep systemic change on the agenda and lived experience feedback central to the service delivery model.

About NHARP

Take Two’s Northern Healing and Recovery Program (NHARP) works with children, young people (aged 0 to 17) and their caregivers who are victim survivors of family violence. The Peer Worker role and lived experience perspective are integrated into the NHARP social justice therapeutic model of care.

About Y-Change

Berry Street’s Y-Change initiative is a social and systemic change platform for young people aged 18 to 30 with lived experiences of socioeconomic and systemic disadvantage. As Lived Experience Consultants, the team works to challenge the thinking and practices of social systems through advocacy and leadership.

Header Image: Photo by Reuben Juarez on Unsplash