How many babies who experience serious hardships in their first year of life have delayed communication skills?

The Berry Street Take Two team based in Bendigo in the Loddon region of Victoria were worried about this. They welcomed a speech pathologist to work with them for more than a year, as part of Take Two’s Communication Project to help understand the scale of the problem.

My time in the Loddon region

I was the speech pathologist fortunate enough to work with the Loddon region Berry Street Take Two clinicians. We discussed problems with communication, language delays and swallowing problems in childhood, and they referred many of the infants and children they are working with to me for assessment. The Communication Project is a three-year pilot project funded by the Kelly Family Foundation. It allows children in out-of-home care, who have been affected by developmental trauma, to access the services of a mental health speech pathologist.

I made 20 visits to the Loddon region and formally assessed 12 children. I wrote my speech and language assessment reports in plain English to make the information accessible to a wide audience. The Take Two clinicians and I held joint feedback sessions with the care team, and the child if appropriate. At these meetings assessment findings were shared and recommendations were discussed. This allowed the carer and clinician to keep communication issues in mind as the broader therapeutic plan progressed. I was available to follow up to refer the child to local clinicians where appropriate, or to advocate for more services where needed.

Overall findings

So, what did we find?

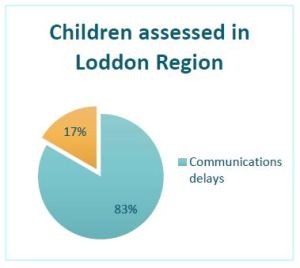

Most of the children (more than 80%) showed clear delays in their communication skills.

Many of the babies were quieter than would be expected, engaging in less vocal play, making fewer sounds and words. They had not learned to synchronise the use of facial expressions and gesture while looking to their carer. They did not respond to their name very reliably. It was, however, encouraging to see that many of the babies were actively exploring their world while showing signs of attachment and trust with their caregivers. Some of the babies were learning to play peek-a-boo, imitate animal sounds, wave bye-bye and show interest in books.

One family’s experience

In one group of three siblings all under three years old and in out-of-home care ─ communication delays proved a common thread. When I first met the siblings, who had all been referred to Take Two, they were each dressed in Aboriginal printed fabrics. The boys were in little hoodies and vests, and their baby sister wore her dot-painted smock over printed leggings. Their Aboriginal carer had lovingly dressed them for their Welcome Baby to Country ceremony to be held later that day.

During the first visit I assessed the two older boys, using the Rossetti Infant-Toddler Language Scales. Later I saw the trio again to assess the youngest, a 16-month-old girl. When interpreting the findings, I needed to adjust the ages of the children, to account for their premature births. It was more accurate to consider the youngest as a 13-month-old, as she was born 12 weeks early. The 22-month-old boy was born four weeks early, and the 34-month-old was born eight weeks early. Their developmental challenges began before birth. Both parents had their own trauma histories and struggled with drug abuse and mental health. Their relationship was marked by violence throughout the pregnancies.

Adverse early life experiences can leave a huge impact on a child’s development. For the eldest child, he was born with a range of medical complications involving cardiac, musculoskeletal and gastro-intestinal problems. His hearing is often impacted by fluid in his middle ear. The youngest child also has cardiac issues, swallowing difficulties and suspected hearing impairment. All three are affected by the drugs they were exposed to in utero and were supported to withdraw from these substances in hospital after birth.

We found access to hospital records to gather this information was complicated because the children had been registered under differing names with Child Protection, metropolitan and regional hospitals. These administrative inconsistencies led to significant system obstacles, which were surprisingly difficult and time-consuming to fix.

We identified that each of the children had clear communication skills delays.

- The 32-month-old’s skills were more like those of a child aged 24-27 months.

- The 21-month-old’s skills were more like those of a child aged 15-18 months.

- The 13-month-old’s skills were more like those of a child aged 9-10 months.

Support provided

The caregiver recognised the importance of helping the three children to grow their words and understanding but needed help to do this. The assessment reports provided a simple guide to help with this and were written so they could be shared with childcare staff.

We talked about the positive engagement the children already have with Aboriginal music, movement and playgroups and how this will continue to build communication skills in a culturally enriched way. We also looked at some helpful video resources on strategies to use in the home. Links to the resources were included in the report so that the caregiver could share them with her teenage children at home.

I spoke to the local community health service speech pathologist to share our recent findings. They had previously been referred one of the children and I encouraged them to resume working with the caregiver now it was known she was supporting three young ones with language delays. I supported the Take Two clinician to continue with advocacy for a developmental paediatrician to review each of the children and be proactive in engaging early intervention services as needed.

Placement with capable and loving caregivers can make an enormous difference for children. While working with these children, I worked with their foster carer. She is a highly skilled Aboriginal woman committed to providing the children with the love, connection and support they need to flourish. Given the children have received more than 12 months of attentive caregiving in this foster family, it’s not surprising that each of the children scored highly on measures of attachment and interaction.

These strong bonds will form a solid foundation for the next developmental gains that the children will need to make.

Overcoming delays often requires extra help

It’s common that children with a history of early trauma and disadvantage have delayed communication skills. Ensuring children are safe and are receiving good-enough caregiving is the first step in addressing developmental trauma. But it’s not enough to overcome developmental delays. A developmental paediatrician can help make sense of and manage co-existing medical concerns, including hearing .

When infants and children have difficulties learning language, their caregivers need clear guidance, modelling, encouragement and support to offer targeted language input that matches the child’s learning needs. Cultural connections offer further richness through identity, belonging, movement, song and stories.

I thank the Kelly Family Foundation for their generous support. If we can invest wisely in the early years, it allows children to flourish once they reach school, sowing seeds for a brighter future.

Take Two is a Victoria-wide outreach service provided by Berry Street on behalf of the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services. The service is recognised all over the world as a leading model of how best to support children and young people who have experienced complex developmental trauma.

Take Two can provide specialist clinical consultancy services to other organisations. Contact us for more information.

By Monica Rowland, Senior Speech Pathologist, Berry Street – Take Two

*Note: Names and other identifying details of the children and their families in our case studies have been changed to protect them. Models appear in our photographs to protect the identity of our clients.