Lots of 7-years-olds wouldn’t be able to tell the difference between a moth and a butterfly. But Jay can.

Jay is an Aboriginal child going to a local primary school in suburban Melbourne. But unlike the others in his class, he has only just started talking.

Jay’s mother’s family has been badly affected by government policies since colonisation, particularly those that saw Aboriginal children forcibly removed from their parents and placed in non-Aboriginal families or orphanages.

Both of Jay’s parents are heavy drug and alcohol users. His dad is very violent, especially towards his mum. They were in their early 20s and both estranged from their own families when Jay was born.

Jay’s parents were homeless and squatting in an unused factory. As a baby and small child Jay was surrounded by drug-affected adults whose chaotic behaviour scared him. They also weren’t able to give Jay the constant care and attention a small child needs. He had barely any interaction with other kids and not much else is really known about what happened during the first five years of his life.

Despite a very unstable home life and having never attended kinder, Jay started school. But right from the start it was obvious he was not OK. Jay frequently fell asleep in class. He would wander out of the classroom and off up the street. He’d never bring any food to school and was unusually small for his age. He would arrive at school on foot and alone.

Jay was also wandering the streets alone at night. After several notifications of risks to his safety, Child Protection removed Jay from the care of his parents.

He was placed into the care of his maternal grandmother in the south-eastern suburbs of Melbourne. When he was dropped off at her house he came with nothing other than the clothes he was wearing.

Having never met or seen Jay before, his grandmother and aunties immediately noticed that he didn’t speak.

Jay was diagnosed as having Selective Mutism, an anxiety disorder where the person is so traumatised or anxious that they aren’t able to speak. Some children aren’t able to speak at school or in certain situations when they are anxious. Jay wasn’t talking to anyone, not even at home to his grandmother, his aunties or his two young cousins who also lived there.

His grandmother also realised he appeared to not know he was Aboriginal or know anything to do with his culture.

Jay was referred by Child Protection to Berry Street’s Take Two program for therapeutic intervention to assist him with his development and relationship struggles. He still wasn’t speaking. He didn’t play with others, not even his cousins who he lived with.

Adam, a senior clinician in Berry Street’s Take Two Aboriginal Team, started seeing Jay every week at his new school. They would spend time together in the classroom after the other students and his teacher had left. Adam deliberately chose to have the sessions in the classroom to reduce the anxiety Jay would likely feel being in another new space.

In the first session, Adam simply sat in the reading corner of the classroom with Jay and flipped through books while talking to him. Adam kept it casual and was careful to not make Jay feel as though he had to reply. Jay was unresponsive and wouldn’t make eye contact, but he did seem to like looking at the books.

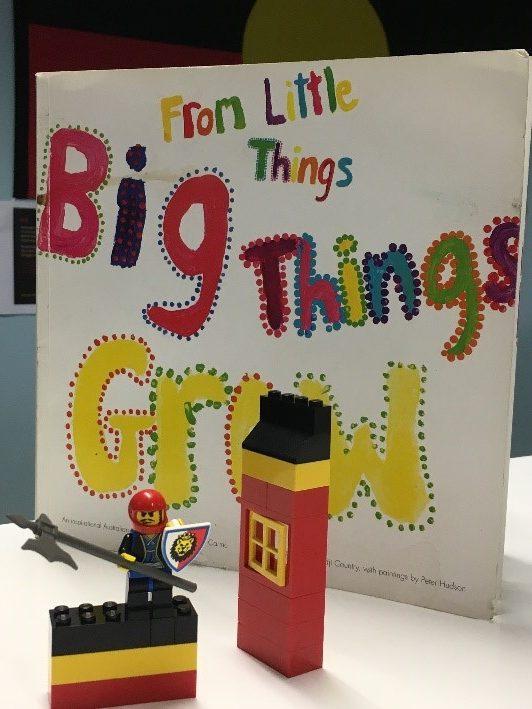

After a couple more sessions looking at books and talking to Jay, Adam brought a box of Lego and started piecing bits together, encouraging Jay to do likewise. Jay picked out a Lego figurine with a helmet, a battle axe and a shield and kept twirling it around in his fingers. Adam named him ‘Little Warrior Jay’ and built an Aboriginal flag podium for him to stand proudly on.

At the end of the session Jay didn’t want to put Little Warrior back into the Lego box. Adam went and got a small cardboard box and put Little Warrior inside and promised to keep him safe for Jay until next week.

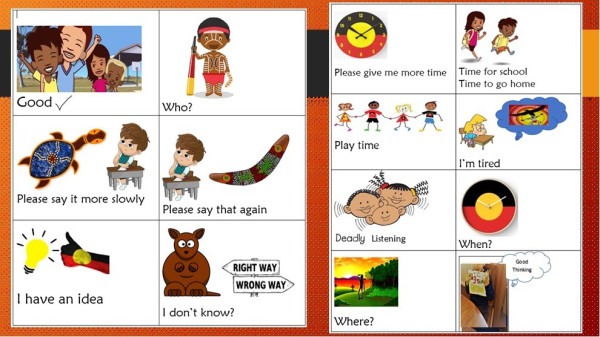

Having never worked with a child with Selective Mutism before, Adam sought a secondary consultation with Take Two’s Speech Pathologist, Monica. She provided Adam with more understanding about the condition and some therapeutic techniques he could try using with Jay. She also provided him with some visual communication cards and encouraged him to explain them to Jay, so he could use them at school and at home.

Adam took the cards and created a new set specifically for Jay which incorporated Aboriginal cultural references. He took them to a session with Jay, explained them to him, and then separately explained them to his grandmother and his teacher. Jay seemed to like them and started using them in the classroom and at home.

Monica also suggested that Adam read to Jay.

They started reading a children’s book of the words of a song by Paul Kelly and Kev Carmody called “From Little Things Big Things Grow”. It’s about a protest that led to the start of the Aboriginal land rights movement and is illustrated with art created by Gurindji kids from the land where the protest happened.

When Adam started reading the book Jay started giggling and looked at Adam’s face. It was the first time Adam heard him make a noise and make eye contact. Adam realised Jay had probably only ever had his female teachers read him stories. He was laughing because he thought it was funny being read to by a man.

Each session Adam continued to read Aboriginal children’s books to Jay. Jay kept picking up From Little Things Big Things Grow and handing it to Adam to read again. It was clearly his favourite. Adam would always bring Little Warrior Jay and the box of Lego to the sessions and ask him how his week had been and relating the questions to Jay’s week at school and at home. Jay started sometimes nodding or shaking his head to reply to Adam.

At home Jay’s grandmother and aunties immersed him in his culture as part of his daily life. They took him and his cousins with them when they back to country for Sorry Business and there he met more aunties, uncles and cousins. They told him some stories from their mob.

As the months passed Adam says he saw Jay change.

His whole affect changed. He was walking taller, his posture changed. He started making eye contact more often and used a lot more gestures. He started smiling and giggling a lot.

As the weather improved, they started doing the therapy sessions outdoors on the school’s grounds together. Sometimes they’d take a footy and kick it. Adam learnt the names of some of the plants, birds and insects in Jay’s traditional language. As they walked Adam would name them in English and would try and say them in Jay’s traditional language too. Jay laughed at him trying to say the words.

As they approached the summer school holidays Adam was explaining to Jay about the Aboriginal seasons and that by watching the plants, animals, insects as well as the weather and the stars in the sky you can see the seasons changing.

As they walked through the school’s kitchen garden Adam spotted an insect flying above the silverbeet and pointed to it:

“Look there’s a butterfly now.”

In a small voice Jay replied to him.

Adam says he was amazed to hear Jay’s voice. But he managed to not break his stride because he was conscious that he would make Jay more anxious if he made a big deal out of the fact that he’d spoken.

“It was so hard to keep talking to him and act as though nothing had happened. But I had to turn direction and keep walking so he couldn’t see the smile on my face.”

For the rest of that session Jay didn’t say anything else. But in every session since he has spoken at least a couple of times to Adam and this is increasing. He’s spoken to his teacher a couple of times at school and to some of his classmates. His grandmother says he now increasingly speaks to her, his aunties and to his cousins.

Adam will continue working with Jay for the moment.

“I know that it was through culture that he found his voice,” Adam says. “He is understanding who he is, where he fits in the world and how he belongs with his mob. I can see him connecting with something bigger than him. I can see he’s feeling like he has a place in the world and an identity he can connect with.”

“I hope he continues to grow to be proud to be Aboriginal – just like Little Warrior Jay is.”

Take Two is a Victoria-wide outreach service provided by Berry Street on behalf of the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services. The service is recognised all over the world as a leading model of how best to support children and young people who have experienced complex developmental trauma.

Take Two can provide specialist clinical consultancy services to other organisations. Contact us for more information.

Note: Names and other identifying details of the children and their families in our case studies have been changed to protect them.