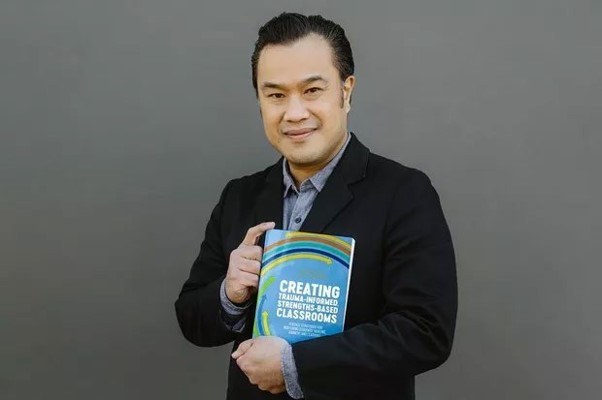

This article was published by EducationHQ, October 2021

The phone line at Berry Street, Victoria’s largest independent child and family services organisation, has been running hot of late – but those seeking the wisdoms of education director Dr Tom Brunzell and his team fall well outside the usual profile pool.

An expert in trauma-informed education, Brunzell has felt the full force of the pandemic work its way into classrooms and staffrooms across the globe. Schools and educators that never have identified as ‘trauma affected’ are reaching out for help.

Luckily, Brunzell has been steeling up the research base for years. We’re absolutely prepared for this, he says.

“It is a time in history that, thank goodness, we were ready for, in terms of our research and experience and practice. It’s a time in history where we can provide answers; that this is not a mystery as to how we need to support schools to create the rhythms, routines and strategies and values that say, ‘Hey, we can harness this research – now is the time.’”

Bolstered by a PhD in trauma-informed positive education, for years Brunzell has worked closely with schools struggling to help children who have been directly impacted by trauma – whether this stems from abuse, neglect, or a traumatic past. These kids might have “very complex and sometimes scary or alarming behaviours”, he says.

“Our approach is always to say, ‘Hey everybody in the school, everyone on staff, you must learn these trauma-informed wellbeing strategies, because these kids deserve it. And we can do better.

“That was before the pandemic.”

Now it’s a whole different ball game, Brunzell says.

Pandemic-induced trauma

“We started getting phone calls from all sorts of schools, not just the schools we would expect working in communities of systemic disadvantage, but all schools: schools serving high-flying kids, independent schools that have very illustrious names and families they work with.

“And what became very clear to us, number one, is that what they were asking for was the following: they said, ‘Listen, we have students who are now acting out and acting in, who weren’t doing those things before. We now have students showing us alarming behaviours inside and outside the classroom. We never thought that our school was a trauma-affected school, but we’re seeing so many behaviours that we just don’t know and want to proactively support’…”

Aware that too many teachers are heading home with an awful sense of emptiness after a day on the job, Brunzell has recently turned his research focus on teacher wellbeing – an area that has “exploded” with interest over the last five years, he says.

The aim has been to tap into a facet remaining relatively untouched by the scrutiny of academia: trauma-informed teacher wellbeing.

How can teachers who have had repeated exposure to child trauma deal with the associated flow-on effects, such as secondary traumatic stress, compassion fatigue and burnout?

Brunzell has some solid evidence-backed ideas on this front.

Stopping the route to teacher burnout

The number one reason our teachers are burning out is because they do not have enough strategies to manage student behaviour

“…and we understand that when a teacher doesn’t have enough strategies, they hold that stress, they have something we call ‘compassion fatigue’ – they just don’t have the resources and the positive feedback that their efforts matter, that their efforts count, that (knowing of) ‘the daily things I’m doing are really paying off’.

“They drive home empty, and they don’t have those reserves of compassion and empathy and care anymore.”

This understanding has been “a real lightbulb for a lot of teachers,” he adds.

“They’re like, ‘Why do I feel burned out? I mean, I feel like I should be [able to do] this’. But when they realise it’s their ethics of care and compassion that has been drained, that can offer a promising pathway to say ‘you’re a normal human being, all of us in a similar situation would feel that same emptiness’.”

Driving practice with data

The educators’ latest paper Trauma-informed Teacher Wellbeing: Teacher Reflections within Trauma-informed Positive Education draws on data unearthed in his PhD.

“The number one headline finding was when it comes to trauma-informed wellbeing, teachers have to model it, they have to live it, they have to realise that this practice is only authentic to students when students really observe that the adult in front of them is practising what they’re preaching, and that the students like how they feel when they’re in this adult’s presence,” Brunzell explains.

Two groups of teachers emerged from the research, he says. One, “the positive, happy group” learned many wellbeing strategies and then decided to apply them in their lives away from school.

“They, on their own, said ‘Hey ... if I have a rupture at home, or I’m frustrated, or I lose my cool, I’ve got to use some of these strategies to practice before I go back in the classroom’.

“And two things happened in that group of teachers – they obviously saw their students’ learning increase, and they saw students doing better in school, but they felt more renewed in the work: their wellbeing increased.”

The second group complained, Brunzell says, and took the view that they wanted to help their students, but didn’t show up at PD or other professional improvement initiatives for themselves.

This was the “I just come to school to teach” cohort, Brunzell notes.

“So we said, ‘OK, that’s cool. You can use these strategies to help the students, and they did and they worked. But these teachers who didn’t practice these strategies (personally) reported lower wellbeing at the end of the year, or negative wellbeing.

“And when we asked them, ‘Why do you think your wellbeing is lower?’ they blamed their principals, they blamed their schools, they blamed too much work.

“And we realised, ‘ah, you didn’t really take this seriously for yourself…”

The way forward

Brunzell holds two grand hopes for his research efforts.

“My smaller hope is that there are not enough universities who are teaching this to pre-service teachers yet. And we have a whole bunch of new teachers who are still burning out, who are complaining they don’t have enough strategies.

“And when I do big presentations at universities and I’ll say, ‘Hey, have you learned this?’ I get blank faces. So… we need the system to wake up and realise if you really want to prepare teachers, you need to give them this kind of research and strategies.”

The “big hope” is that trauma-informed wellbeing comes to form the backbone of how things are done in all schools – and not just those in this country, but “all of them”, Brunzell says.

“…post-whatever the pandemic impacts are going to be, we can’t just do school as usual,” he warns.

“We have to have every staff member around the country realise: you don’t have to lay awake at night wondering what to do. You don’t have to go [down] endless rabbit holes of internet searching or complaining or blaming your principal or whatever it is. There are answers.

“And the many, many schools we’re working with are really increasing their capacity to do just this.”